In the pantheon of cycling, few disciplines possess the raw endurance, drama, and colourful legacy of six-day track racing. Born out of a heady mix of late-19th-century sporting ambition and the public’s growing appetite for spectacle, six-day racing would go on to become one of the most storied formats in professional cycling. With its unique blend of athleticism, strategy, showmanship, and occasionally controversy, the six-day race was once the crown jewel of the velodrome and a cultural event that transcended sport itself.

Origins in the Age of Endurance (1870s-1890s)

The six-day race has its genesis in the age of endurance sports that flourished in the late 19th century. This was an era where the public fascination with human limits gave rise to bizarre and gruelling contests, from pedestrianism (competitive walking) to marathon dance competitions.

In the United Kingdom, cycling was undergoing a period of rapid innovation and growing popularity. The invention of the safety bicycle and improvements in tyre technology made cycling both accessible and fast. Against this backdrop, endurance cycling events began to appear, including the earliest six-day formats.

The first recognised six-day race took place at the Agricultural Hall in Islington, London, in 1878. Cyclist David Stanton rode around a track for 18 hours a day over six consecutive days. This solo feat drew large crowds and established a precedent for what would become six-day racing. Initially, these events were tests of individual stamina: one man, one bicycle, endless laps.

The format migrated to the United States, where it evolved rapidly. By the 1890s, Madison Square Garden in New York City became the spiritual home of the six-day race. These American events mirrored the British endurance roots but took the concept to new extremes, with riders pushing themselves to the brink of collapse. Crowds swelled to witness the spectacle, especially as the races became 24-hour affairs with riders alternating brief naps and meals in the infield.

The Emergence of the Team Format (Early 1900s)

Mounting health concerns and mounting political pressure led to reforms. In 1903, New York authorities outlawed solo 24-hour racing. The sport’s promoters responded ingeniously: instead of one rider, teams of two would alternate riding, ensuring non-stop action without exhausting a single individual.

This innovation was transformative. It preserved the race’s continuous nature while introducing new strategic elements. One rider would rest while the other competed, often rejoining the action via the signature Madison hand-sling, a manoeuvre that propelled the resting partner into the race at full speed.

The team format added complexity, drama, and visual flair. It required not only fitness but also coordination, timing, and tactical nous. It also opened the door to international competition and further professionalisation of the sport.

The Golden Age: 1920s to 1950s

Between the wars and into the post-WWII era, six-day racing blossomed. Europe and North America became hubs for a fully-fledged circuit of events. Riders such as Piet van Kempen, Franco Giorgetti, and later, Rik Van Steenbergen and Fausto Coppi, became stars not just for their road racing but also for their prowess on the boards of the velodrome.

In the UK, six-day events flourished in cities like London, Manchester, and Birmingham. In the US, races in Chicago, Detroit, and New York drew huge crowds and substantial media attention. Riders competed for hefty prize purses, and the atmosphere at the velodromes was electric.

The racing was a blend of multiple disciplines: time trials, sprints, derny races, and Madison chases. Teams accrued points, but crucially, the team with the most laps covered remained king. A single lost lap could nullify a lead in points, keeping the competition open and dramatic until the very end.

This era also saw six-day races become grand social events. The infield became a carnival of food, music, and late-night entertainment. Races often began in the evening and continued into the early hours, allowing spectators to come and go as they pleased. These events were covered by the press not just in the sports pages but also in society columns.

Decline and Near Disappearance (1960s-1980s)

Despite its glamour and popularity, six-day racing began to wane in the 1960s. A confluence of factors contributed to its decline. The rise of television shifted sports consumption away from live events. The advent of the car and changes in urban life meant fewer people cycled and fewer identified with professional cyclists.

Additionally, cycling itself saw a shift in focus. Road racing, particularly the Grand Tours like the Tour de France and Giro d’Italia, became the primary stage for heroics. The velodrome, by contrast, seemed old-fashioned.

In the UK, six-day racing all but disappeared, with the last traditional London Six-Day event held in 1980. Europe, particularly Germany and Belgium, kept the tradition alive but in a reduced form. The US circuit faded almost completely.

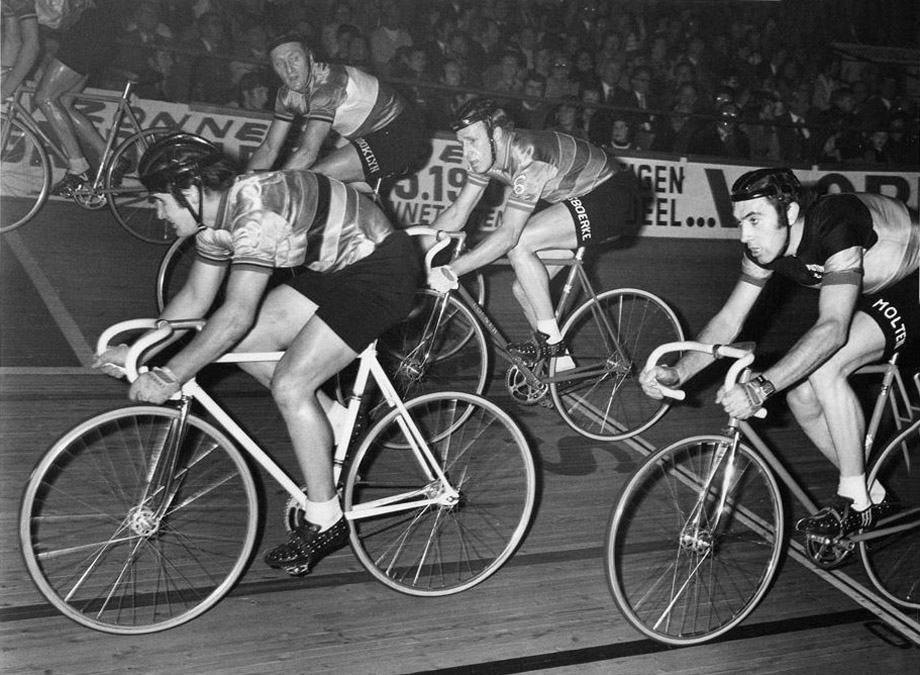

During this time, six-day racing became somewhat of a niche discipline, supported by die-hard fans and older cycling enthusiasts. A few legendary riders kept the flame burning, such as Patrick Sercu, who won an astonishing 88 six-day races, a record that stands to this day.

Revival and Reinvention (1990s-Present)

In the 1990s and 2000s, six-day racing experienced a modest revival, buoyed by changes in sporting culture and the efforts of committed organisers. In Germany, events in Bremen, Berlin, and Munich maintained a loyal following. The success of these races demonstrated that there was still appetite for the format, particularly when presented as part of a broader entertainment package.

In 2016, the Six Day Series was launched with the ambition of creating a global circuit of modern six-day events. Backed by Madison Sports Group, the series introduced updated formats, high production values, and a renewed focus on fan experience. Races featured live music, dramatic lighting, and announcers to explain the action to newer audiences.

London’s Lee Valley VeloPark, built for the 2012 Olympics, became the new home of the London Six Day, reviving a proud tradition and attracting top riders including Mark Cavendish and Iljo Keisse. Other events have taken place in cities like Melbourne, Copenhagen, and Hong Kong, giving the series a truly international scope.

While the modern format differs in some ways from its forebears,most notably, events are often condensed into evening sessions rather than true 24-hour racing,the essence remains: endurance, teamwork, tactics, and relentless action.

The Modern Rider: Athletes and Entertainers

Today’s six-day competitors must be versatile, equally comfortable with the sprint and the chase. Riders like Kenny De Ketele, Roger Kluge, and Jasper De Buyst epitomise the modern six-day star: fast, smart, and charismatic.

Importantly, these riders are not just athletes but performers. They interact with crowds, engage with media, and often ride multiple events per night across a week-long schedule. Their stamina is not only physical but mental.

The format also serves as a proving ground for younger talents and a way for road racers to sharpen their legs during the off-season. For fans, it offers rare access to stars in an intimate and lively setting.

Six-day track racing is one of cycling’s oldest and most fascinating disciplines. From its beginnings as a Victorian endurance novelty to its heyday in the roaring 20th century, and now its revival in the 21st century as a hybrid of sport and show, the six-day race has continually evolved.

While it may never again be the dominant spectacle it once was, its unique blend of endurance, spectacle, and camaraderie ensures that it retains a special place in the world of sport. Its history is a testament to cycling’s capacity for reinvention and to the enduring human love of a great race.

In an era increasingly dominated by screens and fast-paced entertainment, six-day racing offers something refreshingly tangible: the rhythmic whirl of tyres on boards, the slap of the hand-sling, the roar of the crowd, and the eternal chase for one more lap.

Leave a Reply